By Dave Bonan

The ocean contains a system of currents that connects different ocean basins. A significant feature of this system is found in the Atlantic Ocean basin and often referred to as the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC). The AMOC is crucial because it transports warm water northward and helps circulate water between the deep ocean and the surface. As a result, the AMOC plays a vital role in regulating both regional and global climates and can influence weather patterns, such as the African and Indian monsoons, and the summer climate in North America and Western Europe. The AMOC is also believed to play a primary role in shaping the location of tropical rainfall through its effect on northward ocean heat transport. Therefore, understanding the factors that control the strength and structure of the AMOC and how it will change over the 21st century is a central goal of climate science.

Comprehensive climate models predict that the AMOC will weaken significantly over the 21st century, though there is substantial intermodel spread. For example, on average, climate models predict that the AMOC will weaken by approximately 8 Sv (1 Sv \(\equiv 10^6 m^3 s^{-1}\)) across low (SSP1-2.6), medium (SSP2-4.5), and high (SSP5-8.5) emission scenarios (Fig. 1). However, some climate models predict that the AMOC will weaken by as little as 2~Sv, while others predict that it will weaken by as much as 15 Sv (Fig. 1). A weakening of the AMOC could lead to rapid sea level rise off the coast of North America, a sudden and severe drop in temperatures across northern Europe, and serious disruption to monsoons across Asia.

In a new study, we introduce a framework to reduce the intermodel spread in AMOC projections over the 21st century. We leverage a well-known aspect of climate model projections, which shows that climate models with a stronger present-day AMOC exhibit more weakening over the 21st century (compare red and blue lines in Fig. 1). While this aspect of AMOC weakening has been recognized for decades, thus far it has been unclear why climate models exhibit this behavior.

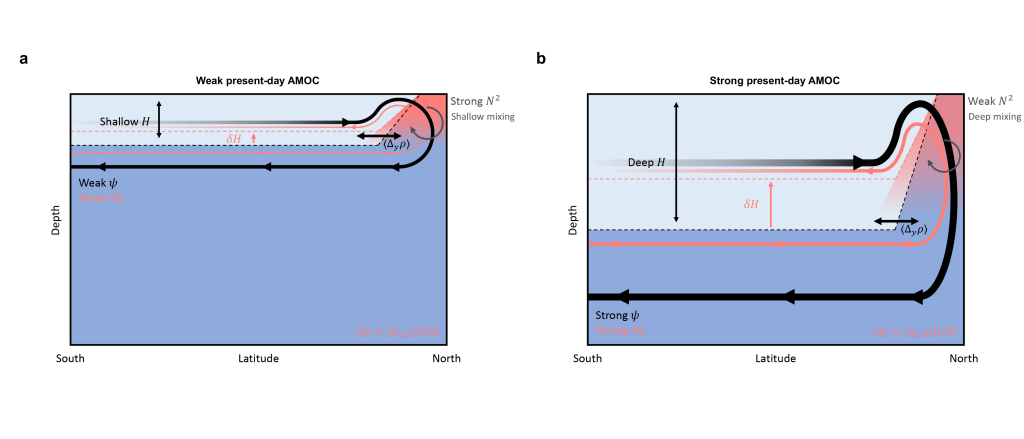

We introduce a physical mechanism that explains why this feature of AMOC projections exists. We show that it is related to the depth of the present-day AMOC. Climate models with a deeper present-day AMOC tend to have a stronger AMOC. A deeper AMOC is also associated with a less stratified North Atlantic, which allows surface properties to enter the interior of the Atlantic basin more easily and affect the AMOC more readily. For example, under warming, a less stratified North Atlantic would allow density anomalies associated with global warming to enter the deep interior of the Atlantic Ocean basin more easily and cause the AMOC to shoal more. This shoaling leads to a weakening of the AMOC, explaining why the present-day AMOC strength is related to its future weakening.

We then develop a simple expression to predict future AMOC changes at the end of the 21st century. Our expression is based purely on the present-day ocean properties, enabling us to use Bayesian statistics to integrate estimates of the observed AMOC strength. These constrained estimates show that the AMOC will likely undergo limited weakening over the 21st century as based on current state-of-the-art climate models. For example, unconstrained projections from climate models suggest the AMOC will weaken by approximately 8 Sv, whereas our constrained estimates suggest the AMOC will weaken by approximately 4 Sv (Fig. 2). Interestingly, our results also show why AMOC weakening looks similar regardless of a low or high emission scenario, as much of the AMOC weakening over the 21st century can be attributed to the present-day ocean state.

The CliMA group uses information from studies like this to inform model development. This work argues that much of the intermodel spread in AMOC weakening can be attributed to biases in simulating the present-day ocean stratification. Thus, to accurately predict the response of Earth’s climate to increasing anthropogenic greenhouse-gas emissions, climate models like CliMA need to accurately simulate processes that impact the present-day ocean state. One key process is ocean eddies, which play a primary role in setting the ocean stratification. The ocean component of CliMA can be run with grid resolution as fine as 10 km for multi-decadal climate simulations, allowing for ocean eddies to be relatively well resolved. This alleviates the need for parameterizing ocean eddies and reduces present-day ocean biases.

Featured image: Schematic depicting the processes linking the present-day and future AMOC strength. a,b (from Bonan et al, 2025)